Create simple hash map with expiration(time-to-live) feature

You want to add & use simple cache in your application via hash map, but also you want your cache to remove automatically expired …

Like people, computers can multitask. They can be working on several different tasks at the same time. A computer that has just a single central processing unit can’t do two things at the same time, but it can still switch its attention back and forth among several tasks. Right now computer has more processing units which means they can work on several tasks simultaneously. To use the these multiprocessing computers, we can do parallel programming. In other words we can write a program (composed of several tasks) that can be executed simultaneoulsy.

Unfortunately, parallel programming is even more difficult than single-threaded programming. We can counter a whole new category of errors. Fortunately Java provides nice API to work with threads easily. In this long blog we are going to learn basics of the thread in the context of Java programming.

In Java, a single task is called a thread

The term thread refers to a thread of control meaning that a sequence of instructions that are executed one after another.

Every Java program has at least one thread. When the Java virtual machine runs our program it creates thread that is responsible for executing the main routing of the program.

In Java, a thread is represented by an object belonging to the class (or subclass of this called) called: java.lang.Thread

The purpose of Thread object is to execute a single method and to execute it just once. Single method represents the task to be done by the thread. The method is executed in its own thread of control.

When the execution of the thread’s method is finished (either normally or throwing exception(s)), there is no way to restart the thread or to use the same Thread object to start another thread.

We create thread by extending Thread class and define the method called run() in the subclass.

run() method defines the task that will be performed by the thread, when the thread is started the run() method will be executed in the thread.

public class AnyThread extends Thread {

public void run() {

System.out.println("Thread execution");

}

}

If we want to use AnyThread, we have to create an object:

AnyThread anyThread = new AnyThread();

However, creating the object does not automatically start the thread (or call the run method). We have to call the start() method in the thread object:

anyThread.start();

The purpose of the start() method is to create the new thread of control that will execute the Thread object’s run() method. The new thread runs with any other threads that already existed.

The start() method returns immediately after starting the new thread of control without waiting for the thread to terminate. This means that the code in the thread’s run() method executes at the same time as the statements that follow after the call to the start() method. For instance:

AnyThread anyThread = new AnyThread();

anyThread.start();

System.out.println("Main method print");

After anyThread.start() is executed, there are 2 threads. One of them will print Main method print and the other will print Thread execution. The most important point is that these messages can be printed in random manner. Because 2 threads run simultaneously and will fight each other to access standart output. Whichever thread happens to be the first to get access will be the first to print its message.

Note: If we were call the run() directly instead of start(), then run method would be run in the same thread. Therefore calling the run or start are so different things …

We can also create a thread by implementing the interface called java.lang.Runnable which defines a single method called public void run(). With a given runnable, we can create a Thread whose work is to execute the Runnable’s run method. We will give the our Runnable implementation to the Thread in the constructor.

public class AnyRunnable implements Runnable {

public void run() {

System.out.println("Runnable execution");

}

}

AnyRunnable anyRunnable = new AnyRunnable();

Thread thread = new Thread(anyRunnable);

thread.start();

System.out.println("Main method print");

// Because Runnable is a functional interface we can also create Runnable object with lambda expression

Thread thread = new Thread(() -> System.out.println("Runnable execution"));

System.out.println("Main method print");

thread.start();

The disadvantage of the Runnable way, it violates the single responsibility for the object.

Even we have one processing unit, we can create many threads as we want. But in this time, all running threads will fight each other for time on the processor and only one thread will run its code at time t. Even in this case there is uncertainty, because we can’t know when the processor switch from one thread to another.(It can be done at unpredictable times)

Actually in the point of view of the programmer, there is no difference between for single CPU or multi-core CPU.

To understand threads, let’s go to the sample example. In our example, we are going to create many threads each of them will count the prime numbers between [2, 5000000]

public class CountPrimeThread extends Thread {

private final static int MAX = 5000000;

private final String id;

public CountPrimeThread(int id) {

this.id = "Thread ID: " + id;

}

@Override

public void run() {

long startTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

int count = countPrimes(2, MAX);

long elapsedTime = System.currentTimeMillis() - startTime;

System.out.println( id + " counted " +

count + " primes in " + (elapsedTime/1000.0) + " seconds.");

}

private int countPrimes(int min, int max) {

int count = 0;

for (int i = min; i <= max; i++)

if (isPrime(i))

count++;

return count;

}

private boolean isPrime(int x) {

if (x <= 1) return false;

int top = (int)Math.sqrt(x);

for (int i = 2; i <= top; i++)

if ( x % i == 0 )

return false;

return true;

}

}

In the main method we are just creating the threads and running them:

public class Test {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int numberOfThreads = 10;

System.out.println("Creating " + numberOfThreads + " threads...");

CountPrimeThread[] worker = new CountPrimeThread[numberOfThreads];

for (int i = 0; i < numberOfThreads; i++)

worker[i] = new CountPrimeThread( i );

for (int i = 0; i < numberOfThreads; i++)

worker[i].start();

System.out.println("Threads have been created and started.");

}

}

Here the sample output from my computer:

Creating 10 threads...

Threads have been created and started.

Thread ID: 9 counted 348513 primes in 3.115 seconds.

Thread ID: 8 counted 348513 primes in 3.356 seconds.

Thread ID: 3 counted 348513 primes in 3.938 seconds.

Thread ID: 4 counted 348513 primes in 3.993 seconds.

Thread ID: 6 counted 348513 primes in 4.147 seconds.

Thread ID: 5 counted 348513 primes in 4.15 seconds.

Thread ID: 0 counted 348513 primes in 4.213 seconds.

Thread ID: 7 counted 348513 primes in 4.283 seconds.

Thread ID: 1 counted 348513 primes in 4.309 seconds.

Thread ID: 2 counted 348513 primes in 4.316 seconds.

The second line (Threads have been created and started. ) was printed immediately. At this point main program(main thread) has ended but the other 10 threads continued to run. After (almost) 4 seconds, all threads completed their run methods. But the order in which the threads complete is not the same as the order in which they were started, and the order is indeterminate. That means if we run the application again the order could be (probably) different. Now let me show you the output with different thread numbers:

Creating 1 threads...

Threads have been created and started.

Thread ID: 0 counted 348513 primes in 1.851 seconds.

Creating 2 threads...

Threads have been created and started.

Thread ID: 0 counted 348513 primes in 1.778 seconds.

Thread ID: 1 counted 348513 primes in 1.787 seconds.

Creating 4 threads...

Threads have been created and started.

Thread ID: 1 counted 348513 primes in 2.101 seconds.

Thread ID: 3 counted 348513 primes in 2.136 seconds.

Thread ID: 0 counted 348513 primes in 2.248 seconds.

Thread ID: 2 counted 348513 primes in 2.255 seconds.

Creating 8 threads...

Threads have been created and started.

Thread ID: 7 counted 348513 primes in 3.07 seconds.

Thread ID: 5 counted 348513 primes in 3.372 seconds.

Thread ID: 6 counted 348513 primes in 3.398 seconds.

Thread ID: 1 counted 348513 primes in 3.477 seconds.

Thread ID: 4 counted 348513 primes in 3.487 seconds.

Thread ID: 3 counted 348513 primes in 3.502 seconds.

Thread ID: 2 counted 348513 primes in 3.559 seconds.

Thread ID: 0 counted 348513 primes in 3.593 seconds.

Creating 16 threads...

Threads have been created and started.

Thread ID: 13 counted 348513 primes in 4.321 seconds.

Thread ID: 15 counted 348513 primes in 5.852 seconds.

Thread ID: 4 counted 348513 primes in 5.965 seconds.

Thread ID: 1 counted 348513 primes in 6.211 seconds.

Thread ID: 12 counted 348513 primes in 6.229 seconds.

Thread ID: 11 counted 348513 primes in 6.451 seconds.

Thread ID: 2 counted 348513 primes in 6.527 seconds.

Thread ID: 10 counted 348513 primes in 6.482 seconds.

Thread ID: 14 counted 348513 primes in 6.603 seconds.

Thread ID: 0 counted 348513 primes in 6.708 seconds.

Thread ID: 8 counted 348513 primes in 6.67 seconds.

Thread ID: 7 counted 348513 primes in 6.725 seconds.

Thread ID: 3 counted 348513 primes in 6.774 seconds.

Thread ID: 6 counted 348513 primes in 6.821 seconds.

Thread ID: 9 counted 348513 primes in 6.863 seconds.

Thread ID: 5 counted 348513 primes in 6.978 seconds.

Creating 32 threads...

Threads have been created and started.

Thread ID: 13 counted 348513 primes in 8.244 seconds.

Thread ID: 20 counted 348513 primes in 8.598 seconds.

...

Thread ID: 28 counted 348513 primes in 9.06 seconds.

Thread ID: 15 counted 348513 primes in 10.168 seconds.

...

Thread ID: 31 counted 348513 primes in 10.828 seconds.

Thread ID: 24 counted 348513 primes in 10.949 seconds.

Thread ID: 18 counted 348513 primes in 11.022 seconds.

Thread ID: 27 counted 348513 primes in 10.916 seconds.

...

Thread ID: 17 counted 348513 primes in 11.275 seconds.

Thread ID: 26 counted 348513 primes in 11.28 seconds.

Thread ID: 29 counted 348513 primes in 11.308 seconds.

...

Thread ID: 3 counted 348513 primes in 12.073 seconds.

Thread ID: 9 counted 348513 primes in 12.085 seconds.

Thread ID: 5 counted 348513 primes in 12.138 seconds.

...

Thread ID: 4 counted 348513 primes in 12.288 seconds.

Process finished with exit code 0

According to the outputs, it seems using the less threads(especially <8) takes little time. Actually the reason is related to the my computer. Because my computer has 8 CPUs (you can learn the number of CPUs by running the command lscpu on your linux system), if i increase the number of threads more than 8, then threads will fight each other to run their codes on the CPUs. And definitely one (or more threads) will wait for other threads. Therefore it will take more times. (IMPORTANT NOTE: Even creating the 2 threads, operating system may run the threads on one CPU -even there are 8 CPUs available!!!-, we can’t know exactly what would happen !!! ). Each processor runs one thread for a a while then switches to another thread(context switches) and runs that one for a while and so on…

Now, let’s look at the Thread and related class called Runtime

We can find the available processor by calling methods on the Runtime class. We may use the Runtime class on Java program to get information about the environment in which it is running. Here is the code for available processors:

public class Test {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int numberOfCPUs = Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors();

System.out.println("Number of CPUs: " + numberOfCPUs);

}

}

Actually

Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors()returns the number of processors available to the JVM. Therefore sometimes number from the method could be different than number of CPU in the system

Once a thread has been started, it will continue to run until its run() method ends.

We can get whether the thread is alive or not by calling isAlive() method. (For instance: anyThread.isAlive())

After the thread has terminated it is said to be killed. And also when a thread has terminated can’t be restarted

We can stop the execution(actually sleep to execution) by calling the static method called Thread.sleep(milliseconds). A sleeping thread is still alive, but it is not running. And while thread is sleeping, computer can work on any other threads (or on other programs). And if you observe (already), sleep method throws an exception called InterruptedException. This exception is thrown when a thread is interrupted while it is sleeping. Therefore we have to write Thread.sleep() in the try ... catch block.

One thread can interrupt another thread to wake it up when it is sleeping or paused for certain other reasons. For instance if we have an object thread with type of Thread, then this object can be interrupted by calling the method: thread.interrupt(). By calling this method we can send a signal from one thread to another.

A thread knows it has been interrupted when it catches an InterruptedException

Sometimes, we have to wait for another thread to die. We can do this by calling join() method. If we have an thread object called thread, then if another thread object thread2 calls the thread.join(), then thread2 will go to sleep until thread terminates. The join() also throwns an InterruptedException, we have to write thread.join() in the try ... catch block. join() can also take maximum number of milliseconds to wait. A call to thread.join(m) will wait until either thread has terminated or until m milliseconds have elapsed (or until the waiting thread is interrupted).

a daemon is a computer program that runs as a background process, rather than being under the direct control of an interactive user.

We can also set the thread as deamon thread by calling thread.setDaemon(true). (But we should do this before calling the start() method of the thread)

Actually Java offers two types of threads: user threads and daemon threads

Deamon threads is used to provide some services to user threads. And because they are serving to the user threads, after all user threads are done, deamons threads will be terminated automatically by the JVM

Every thread has also priority (specified as an integer). A thread with a greater priority value will be run in preference to a thread with a smaller priority. This can be useful especially for GUI programs. We can set the thread priority by calling the thread.setPriorprity()

However we can not set the random integer. Integer value must be the range between Thread.MIN PRIORITY and Thread.MAX PRIORITY

We can also get the current thread by calling the static method Thread.currentThread(). This method returns a reference to itself.

In the multi-thread program the problem arises when threads have to interact with the same sharing resources. Consider the following statement:

count = count + 1;

This operation is actually composed of 3 operations:

And suppose that each thread performs these 3 steps. Remember, it’s possible that processor to switch from one thread to another at any point. (And also running the code simultaneously).

Suppose that while one thread is between Step 2 and Step 3, another thread starts executing the same sequence of steps.

Since the first thread has not yet stored the new value in count, the second thread reads the old value of count and adds one to that old value.

Both threads have computed the same new value for count, and both threads then go on to store that value back into count by executing Step 3.

After both threads have done so, the value of count has gone up only by 1 instead of by 2!. This type of problem is called a race condition.

NOTE: A race condition generally happens in the “Check-and-update” cases

A race condition occurs when two or more threads can access shared data and they try to change it at the same time. For the our count example, the first thread is in a race to complete all the steps (totally 3 steps) before it is interrupted by another thread.

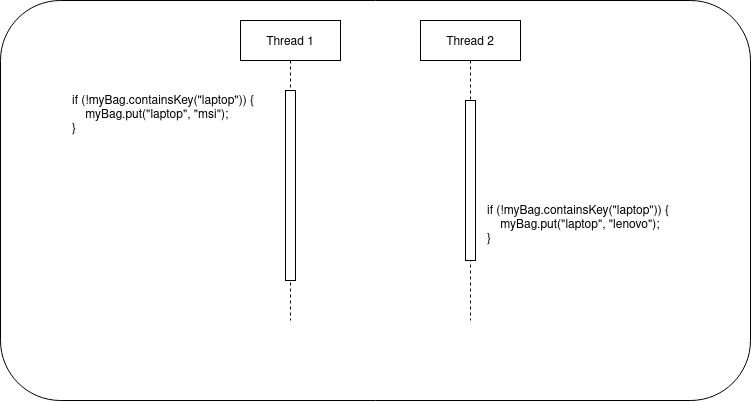

Let’s do it an another example to understand better. Let’s say we have the following java code:

private Map<String, String> myBag = new HashMap(); // shared variable

// thread 1's run method

if (!myBag.containsKey("laptop")) { // instruction 1 (for thread 1)

myBag.put("laptop", "msi"); // instruction 2 (for thread 1)

}

// thread 2's run method

if (!myBag.containsKey("laptop")) { // instruction 1 (for thread 2)

myBag.put("laptop", "lenovo"); // instruction 2 (for thread 2)

}

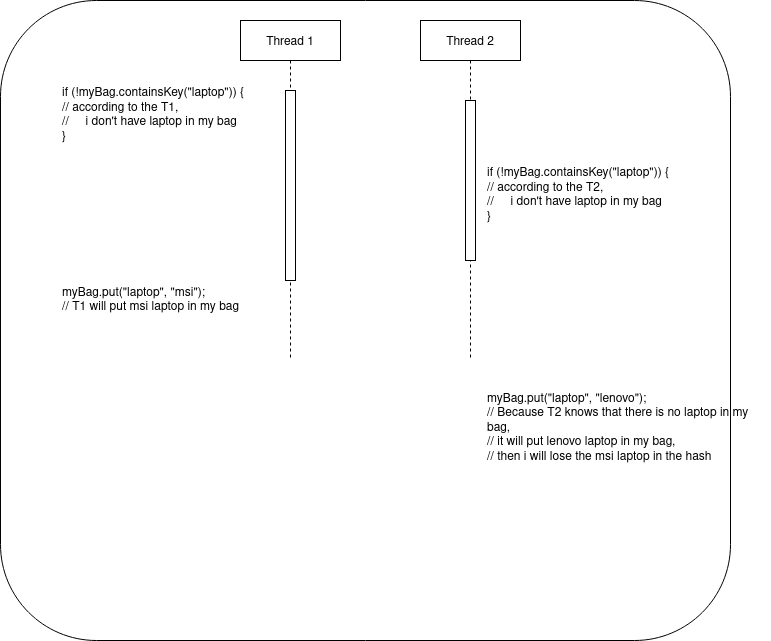

And two threads are trying to put value with the same key but different values. Because we can’t know the which operation will be done at time n, computer may run the following instructions:

With this case we have no problem, becase I have already a msi-laptop, i don’t need to add another laptop in my bag.

However computer may run the following instructions as well:

Now with this case, even i know that i added msi laptop in my bag, it will be changed by the second thread (because T2 knows(or we can say assumes) that there is no laptop).

We can solve this problem by giving exclusive access to a thread. In Java we can do this by using synchronized keyword.

synchronized is used to protect shared resources by making sure that only one thread at a time will try to access the resource. And once a thread starts executing statements inside the synchronized keyword, it is guaranteed that it will finish executing it, until the finish time no other thread can access it.

For our counter example, we can wrap the counter operation in the class with synchronized keyword:

public class MyCounter {

private int count = 0;

synchronized public void increment() {

count = count + 1;

}

synchronized public int getValue() {

return count;

}

}

public static void main(...) {

MyCounter myCounter = new MyCounter();

thread1.run(() => myCounter.increment());

thread2.run(() => myCounter.increment());

}

With this way, we guarantee that increment operation will be done only one thread at a time.

However there can be also a race condition according to the other operation(s) related to the count value. For instance:

if (myCounter.getValue() == 10) {

doSomething();

}

This code block is also vulnerable to race condition, because there is chance for thread2 to change counter (myCounter.increment()) while thread1 is executing the if’s body. To resolve that we can update the code like:

synchronized(myCounter) {

if (myCounter.getValue() == 10) {

doSomething();

}

}

In general the rule of synchronization is:

Two threads cannot be synchronized on the same object at the same time. In other words:

Synchronization is implemented using synchronization lock. Every object has a synchr. lock, and that lock can be held by only one thread at a time.

To enter a synchronized statement or synchronized method, a thread must obtain the associated object’s lock.

If the lock is available, then the thread obtains the lock and immediately begins executing the synchronized code.

Thread releases the lock after it finishes executing the synchronized code.

Although synchronization can help us to prevent race conditions, it introduces another error called deadlock

Consider two chefs need cup and milk at the same time to cook. Let’s assume that chef1 grabs the milk (with adding synchronization lock) and the other (chef2) grabs the cup.

In software world, deadlock can occur if two threads need to lock on the same two objects (like milk and cup).

In general, communication with sharing variables among thread can be done with synchronized methods or synchronized statements. However, synchronization is fairly expensive. And also in some cases, thread may only refer to shared variables without synchronizing their access to those variables.

The other problem (even it is rare) can be seen after a shared variable updated (or set) by one thread(T1) and used in another thread (T2). Because threads are allowed to cache shared data, threads can keep theirs own local copy of the shared data, then thread T2 may not see the changes (done by T1) immediately.

Actually it is safe to use shared variable in a synchronized method (or statements) and there will be no problem (for instance caching the data), it is guaranteed that if in the synchronized method value is changed by T1, then T2 will get the new data AS LONG AS SYNCHRONIZATION OPERATION IS DONE ON THE SAME OBJECT

If we want to use a shared variable safely outside of synchronized code, the shared variable must be declared as volatile. For instance:

private volatile int count;

In other words, any change that is made to the variable will immediately visible to all threads.

Be careful, using a only volatile variable doesn’t solve race condition. Because there is chance to be interrupted by another thread(T2), while thread T1 is incrementing the counter.

Also be aware of that only the variable itself is volatile not the contents that the variable points to. Therefore it is good to declare simple types or immutable types (such as String) as volatile variables.

We can use volatile variables to send signal from one thread to another.

In the parallel programming generally problem arises when we have statement like count = count + 1. Because that statement contains 3 operations there is chance for interruption by another thread while the current thread is running the statement.

atomic operation is something that can’t be interrrupted. It is all-or-nothing. Atomic operation can’t be done partly.

Java provides class called java.util.concurrent.atomic for the simple types. We can use atomic types without synchronized keyword. For instance, we can define an AtomicInteger:

AtomicInteger count = new AtomicInteger();

count.addAndGet(num)

When Thread wants to add num to the count, it can use the addAndGet method. This is an atomic operation which can’t be interrupted by another threads.

However be careful about atomic variables, because atomic variables doesn’t solve all race conditions. For instance the following condition may suffer from the race condition:

int currentCounter = counter.addAndGet(x);

System.out.println("Current count is " + currentCounter);

Because it is possible while output statement is executed, the total counter could have been changed by another thread.

If we summarize:

In parallel programming, we are just dividing our tasks to more subtasks that can be handled by different processors. At the end we are aiming to reduce the spending time. But let’s assume that we divide tasks into 2 subtasks but second task takes too much time rather than first task 1 and let’s assume that computer, running the threads, has only 2 CPU and we assume that each thread is working on different CPU. Now because second task needs too much time (on CPU-2), even CPU-1 is empty (assume that first task’s operation is done) we can’t use the it. Instead of reducing the computational time by half, we are just waiting CPU-2. Therefore we should do the followings:

While the first one is depends on your architecture, we can do that the second one by using the concept thread pools.

Now our aim is keeping the CPU busy as much as possible. To do that we have to assign subtask if there is any available processor(s). In other words, we should do load balancing, the computational load should be balanced among the available processors in order to keep them all as busy as possible.

We know that there is run() method to run thread’s task. However in this case, thread must know its task before starting itself. Well, instead of assinging tasks to threads, we can assing threads to tasks. There can be tasks pool then each thread will get the task from the pool and run it.

Then, we have to create many threads and assing tasks to them. When several threads are available for performing tasks, those threads are called a thread pool. We will use thread pool to avoid creating a new thread for each task. When a task needs to be performed, it can be assigned to any idle thread in the pool. And if all threads are working on theirs tasks, any additional task waits until one of threads in the pool becomes idle. Actually this is queue. When new task available we are adding to the queue, after thread execute the task we are removing from the queue.

As you can guess, because queue will be shared among all threads, there is chance to encounter race condition. (For instance, two threads may get the same tasks and perform the same operation twice). Then synchronization is essential.

Java provides nice API to work with thread pool. It is called ExecutorService

Executors.newFixedThreadPool(n) (where n is the number of threads in the thread pool) …For instance if we want to run one thread per available CPU:

int processors = Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors();

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(processors);

executor.execute(task) can be used to submit a Runnable object, task, for execution.

executor.shutdown() tells the thread pool to shut down after all waiting tasks have been executed.

ExecutorService can also be represented by objects of type Callable<T>, which is a parameterized functional interface that defines the method call() with no parameters and a return type of T. A Callable represents a task that outputs a value.

A Callable, c, can be submitted to an ExecutorService by calling executor.submit(c). The Callable will then be executed at some future time. We can get the value by using Future<T> The method executor.submit(c) returns a Future that represents the result of the future computation.

A Future defines several methods:

future.isDone(), which is a boolean-valued function that can be called to check whether the result is availablefuture.get(), which will retrieve the value of the future. The method future.get() will block until the value is available. It can also generate exceptions and needs to be called in a try..catch statement.For instance, we can refactor our prime number counter with the Executor, Callable and Future:

public class CountPrimeExecutor {

private final static int START = 5000000;

// ...

private static int countPrimes(int min, int max) {

int count = 0;

for (int i = min; i <= max; i++)

if (isPrime(i))

count++;

return count;

}

private static boolean isPrime(int x) {

if (x <= 1) return false;

int top = (int)Math.sqrt(x);

for (int i = 2; i <= top; i++)

if ( x % i == 0 )

return false;

return true;

}

}

public class CountPrimeExecutor {

// ...

private static class CountPrimesTask implements Callable<Integer> {

private final int min;

private final int max;

public CountPrimesTask(int min, int max) {

this.min = min;

this.max = max;

}

@Override

public Integer call() throws Exception {

return countPrimes(min, max);

}

}

}

public class CountPrimeExecutor {

private final static int START = 5000000;

public static void main(String[] args) {

// do not add too many subtasks, it may lead to overload on the CPUs

int numberOfTasks = 100;

System.out.println("\nCounting primes between " + (START+1) + " and "

+ (2*START) + " using " + numberOfTasks + " tasks...\n");

long startTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

// size of a subtask

double increment = (double)START/numberOfTasks;

// create fixed thread pool

int processors = Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors();

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(processors);

// create list to store Futures

List<Future<Integer>> results = new ArrayList<>();

int min = START+1; // The start of the range of integers for one subtask.

int max; // The end of the range of integers for one subtask.

for (int i = 0; i < numberOfTasks; i++) {

max = (int)(START+1 + (i+1)*increment);

if (i == numberOfTasks-1) {

max = 2*START;

}

CountPrimesTask oneTask = new CountPrimesTask(min, max);

// available thread(s) will get the new task immediately after we submit it.

Future<Integer> oneResult = executor.submit(oneTask);

// Save the Future representing the (future) result.

results.add(oneResult);

min = max + 1;

}

// Executor has to be shut down

executor.shutdown();

System.out.println("Shutdown has called waiting for all subtasks ...");

// get the total result from each task's result

int total = 0;

for ( Future<Integer> res : results) {

try {

total += res.get(); // Waits for task to complete!

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println("Error occurred while computing: " + e);

}

}

long elapsedTime = System.currentTimeMillis() - startTime;

System.out.println("\nThe number of primes is " + total + ".");

System.out.println("\nTotal elapsed time: " + (elapsedTime/1000.0) + " seconds.\n");

}

private static class CountPrimesTask implements Callable<Integer> {/* ...*/}

private static int countPrimes(int min, int max) { {/* ...*/}}

private static boolean isPrime(int x) {/* ...*/}

}

Here is the result after running the code in my computer:

Counting primes between 5000001 and 10000000 using 100 tasks...

Shutdown has called waiting for all subtasks ...

The number of primes is 316066.

Total elapsed time: 0.699 seconds.

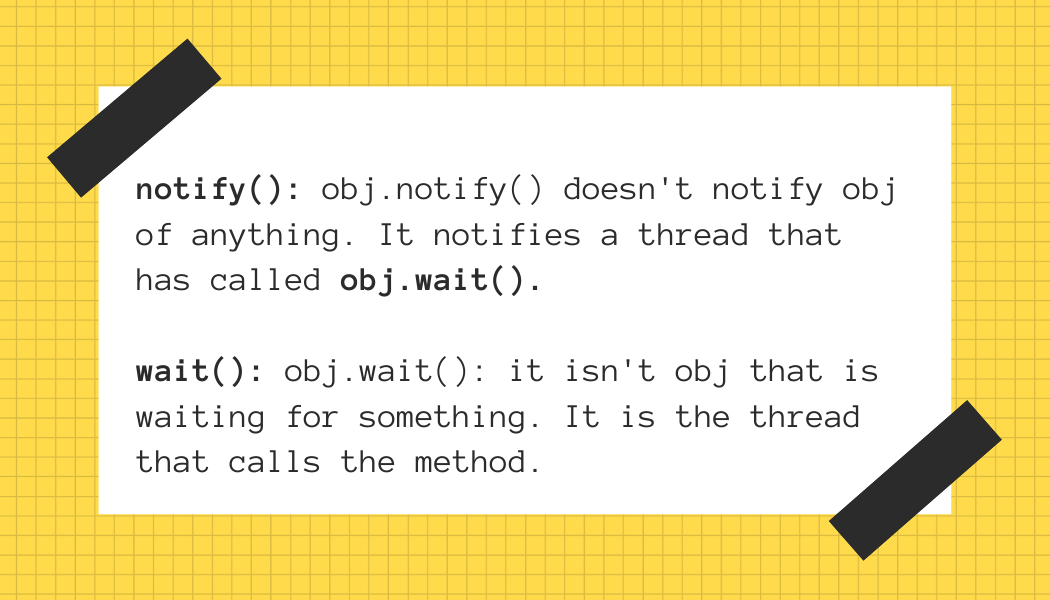

Let’s talk about how we can send notification from one thread to another using wait() and notify()

Sometimes, a second thread has to be wait answer from first thread. This can impose some restrictions such as order of threads.

If a second thread needs to get result from first thread and there is no result, then second thread have to stop and wait for the result to be produced. When the result is ready and second thread is notified, then it can continue its execution.

Java provides methods on the Object class called wait() & notify()̀.

These methods (wait and notify) are low-level, error-phone. It would be better to use higher-level control strategies such as blocking queue.

wait can also be called with

wait(milliseconds)=> wait until amount of milliseconds

When a thread calls a wait() method in some object, that thread goes to sleep until the notify() method in the same object is called.

It is not an error to call notify() when no one is waiting; it just has no effect.

For instance, Thread A can execute the following code:

if (!isResultAvailable()) {

obj.wait() // wait for notification

}

doSomethingWithResult(); // otherwise execute the code

and thread B can have the following code;

generateTheResult();

obj.nofity();

Even these codes seem simple, there is race condition when:

The solution is to enclose both Thread A’s code and Thread B’s code in synchronized statements. Also Java makes an absolute requirement to call notify and wait in the synchronized statements

Let’s do it a simple example:

sharedResult that is used to transfer the result from the producer thread to the consumer thread.

Now let’s use variable named lock for synchronization. The code for the producer thread could be like this:

result = generateResult(); // Not synchronized!

synchronized(lock) {

sharedResult = result;

lock.notify();

}

The code for the consumer thread could be like this:

synchronized(lock) {

while ( sharedResult == null ) {

try {

lock.wait();

}

catch (InterruptedException e) {

}

}

useResult = sharedResult;

}

useTheResult(useResult); // Not synchronized!

Since sharedResult is a shared variable, all references to sharedResult should be synchronized, so the references to sharedResult must be inside the synchronized statements

Well, you may say that if consumer thread will wait for the result after synchronized on the lock, then how consumer thread will release the synchronization lock to give a chance to producer thread to produce result?. In fact, lock.wait() is a special case: When a thread calls lock.wait(), it gives up the lock that it holds on the synchronization object.

Instead of one sharedResult, there could be many shared variables between many producers and consumers. Now here is the simple implementation for that:

public class MyLinkedBlockingQueue {

private LinkedList <Runnable> taskList = new LinkedList <Runnable> ();

public void clear() {

synchronized(taskList) {

taskList.clear();

}

}

public void add(Runnable task) {

synchronized(taskList) {

taskList.addLast(task);

taskList.notify();

}

}

public Runnable take() throws InterruptedException {

synchronized(taskList) {

while (taskList.isEmpty())

taskList.wait();

return taskList.removeFirst();

}

}

}

Finally if you want to notify all the threads that is waiting on obj, you have to use obj.notifyAll(). Because obj.notify() will notify only one of the threads that is waiting on obj.

You want to add & use simple cache in your application via hash map, but also you want your cache to remove automatically expired …

Almost every blog(s) on the Internet for caching operation in the Spring Boot are using @Cacheable, @CacheEvit, @CachePut vs… In this blog we …